We are all confronted with stress of many kinds throughout our daily lives and in the context of training and fitness, we are creating challenges for ourselves that cause stress to our bodies. So, let’s look at the optimal nervous system response in the context of our cortisol levels. As a stress hormone, cortisol is valuable in mobilizing energy for us to meet immediate challenges, but it can have negative consequences when it stays in the nervous system too long.

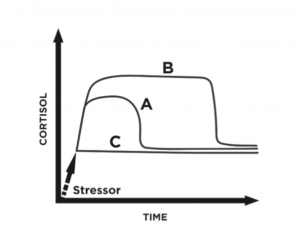

The following graph, adapted from Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers by Robert Sapolsky ¹ uses cortisol levels to show how the nervous system responds to stress:

In this graph, line A is the goal. Following line A, the sympathetic nervous system rises to meet a challenge, like a workout or a high-stakes situation. Once the person has dealt with that challenge, the parasympathetic nervous system takes over, allowing the body to replenish energy, restore balance, and rebuild muscle as it recovers. This is a healthy cortisol response. This is how we want the nervous system to function.

Line B represents an unhealthy cortisol response, not to mention one of the most common health problems in modern society: remaining in a stressed-out, fight-or-flight state for too long. This is what it looks like when the sympathetic nervous system gets triggered and can’t find its way back to rest-and-digest mode. In this state, cortisol levels go high and stay high.

Line C in the graph represents someone who remains in a parasympathetic state (i.e., at a low cortisol level), regardless of the stress or challenge. This low cortisol level can indicate a freeze response, where the nervous system is so depleted it’s unable to mount a response to a stressor. At the other extreme, it can also indicate a high level of nervous system resilience, as in a Special Forces operator in the military who’s trained to respond to challenges without needing to rely on a jolt of stress hormones.

If line A in the graph is the goal, what can we do to condition the body for a healthy cortisol response—and help the nervous system function at an optimal level?

It starts with building resilience or increasing the threshold for transition between the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems. The greater this threshold, the easier it is for the body to handle stress and challenges and remain in a healthy neurophysiological state. This allows the body to save its sympathetic resources for when they’re truly needed.

Building resilience for optimal nervous system function

When it comes to training, building resilience is at the core of the NeuFit® Method. However, before we explore best practices around building nervous system resilience, it’s important to clarify what we mean by resilience in the context of a neurological approach to fitness training.

As we’ve explored in past blogs, resilience is defined as the ability to handle more significant levels of load or challenge without being thrown off course. In terms of training, being thrown off course could mean getting injured (or re-injured).

It could also mean compensating in movement or body position, as when someone is lifting too much weight in a bicep curl and has to arch their back to pull the weight to the top of a rep.

Psychologically, being thrown off course involves losing focus, having a short temper (and reacting to certain situations in ways we later regret), or “choking” in a high-pressure situation, on or off the field.

To help people stay the course, our training approach focuses on increasing the level of load and challenge while minimizing the risk of injury. Working from the client’s baseline capacity, we methodically raise the functional capability of their entire system over time—all in the interest of building resilience.

When it comes to training, the concept of resilience is straightforward. At the same time, our training methods integrate several different dimensions of resilience. These include strength, resistance to injury, resistance to environmental stressors (like temperature changes), and the capacity to deal with psychological stress (i.e., mental resilience). We will examine each of these in our upcoming blogs.

Let’s charge forward to better outcomes together!