In our last blog we began our discussion of the NeuFit® Method for elite athletic performance. This week, we are going to explore this further by introducing neurological training principles that apply to elite athletic training starting with overtraining and the specificity of adaptation. In an upcoming blog we will discuss the performance pyramid.

Overtraining

The principle of overtraining is simply about pushing the body beyond past levels of performance so it can adapt to new levels of challenge.

If an athlete wants to improve, they actually need to create a deficit in the body—and do it consistently. Why? Creating a deficit in the body through overtraining changes their neurological programming.

Overtraining helps the brain understand that there’s a survival benefit to adaptation. The brain responds to overtraining by super compensating – in other words by upgrading the body’s systems and structures. Instead of conserving resources in the short term, the brain sees that it’s worth investing resources to increase the body’s energy supply and build up strength in all the tissues being challenged through training— and it adapts accordingly.

Specificity of Adaptation

Adaptations like building muscle, reorganizing neurological pathways, or forming a callus on the skin all require energy and raw materials. Because the body has a significant amount of work to do just to maintain itself, the brain will only invest additional energy and resources if it’s clear that these investments are contributing to survival.

What drives the brain to invest and adapt in this way? It comes down to a straightforward cost-benefit analysis.

For example, if you lift a barbell one time and it irritates the skin on your hand, it won’t be enough for the body to understand that it’s worth investing resources toward laying down new skin proteins and building a callus.

On the other hand, if you lift a barbell three times a week for several months, then you cross a threshold. Because you’re lifting the barbell consistently, the brain understands that channeling resources toward building that callus will be worth the investment—and yield more benefits than costs over time.

Overtraining on the Bell Curve

When we’re working with individual athletes to improve performance, it’s helpful to treat exercise the way doctors treat prescriptions. Before a doctor writes a prescription, they need to ensure that it’s addressing the right problem (specificity)— and that it contains the right amount (dose).

Just as doctors can prescribe the wrong medicine for a particular health problem, coaches and clinicians can select the wrong exercises for a particular athlete.

On top of that, they can prescribe the wrong dose of exercise. Sometimes, they ask athletes to do too little, where they don’t trigger any meaningful adaptations. Sometimes, they have them do too much, working out to the point where their form breaks down or where they can’t maintain peak speed or strength.

In any training program, but especially when it comes to elite performance, there’s an optimal amount of work, or exercise dosing, an athlete needs to do to gain maximum benefit from overtraining.

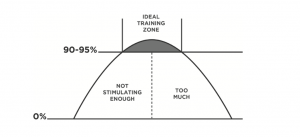

At NeuFit®, when we’re working to determine the optimal exercise dose for an athlete, we think in terms of a bell curve. Consider the following image of a bell curve of performance during a training session.

On this bell curve, the left side represents an athlete who trains too little to stimulate meaningful nervous system adaptations. (We sometimes call this a state of being “under stimulated.”) The right side shows an athlete who trains too much, working out past the point of excessive fatigue or breakdown—and opening the door to negative neurological adaptations that inhibit performance.

The peak of the bell curve represents the optimal amount of overtraining. This is the point where workouts create a deficit in the body that stimulates positive neurological and physiological adaptations.

We’ll continue our focus on overtraining in our upcoming blogs starting with determining the optimal amount of overtraining. Until then…

Let’s charge forward to better outcomes (through overtraining) together!